Speech of Louis-Joseph Papineau for a public meeting at the Bonsecours market

Wednesday night, on April 5, 1848, there was a great meeting in the grand room of the Bonsecours Market (that could welcome more than 12,000 people) to deal with the question of townships.

"At the fixed hour, the room was full and an immense crowd was still pushing with fury at the entrance; the eagerness was such that a few thousand people were forced to regain their residences, despairing to be able get in. A good number of ladies who had gone early enough to obtain a seat and seeing this unaccustomed tumult, feared being crushed by the crowd pushing on the last rows of seats and thus several of them felt the need to leave in spite of their desire to attend the meeting. We consider it regrettable that the seats reserved for the ladies were not better protected. The agitation which produced this movement prevented, for some time, to hear the first speakers. The assembly was made up of all that Montreal has of individuals distinguished by their virtues, their lights, their talents; it represented the very whole of the French-Canadian nationality."

The goal of the meeting was to counter the emigration or the assimilation of the citizens of French extraction; what is at stake, "is the existence of this nationality which is compromised by the loss of a quantity of its members who would be able to give it energy, richness and strength, were they not leaving to be lost and to disappear in a nationality foreign and enemy."

One could observe the presence of Mgr. Ignace Bourget, of many members of the clergy. Pierre Blanchet acted as secretary; the principal members of this association are Joseph Roy, Romuald Trudeau, Édouard-Raymond Fabre, Jean-Baptiste Meilleur, Jean Bruneau, Alfred Pinsonnault, Jacques Viger, Louis Perrault, Joseph-Ubalde Beaudry, Charles-Emmanuel Belle, Magloire Lanctot, Joseph Grenier, Généreux Peltier, Émery Coderre, d'Orsonnens, Joseph Doutre, Labrèche-Viger, James Huston, Charles Laberge and Denis-Émery Papineau.

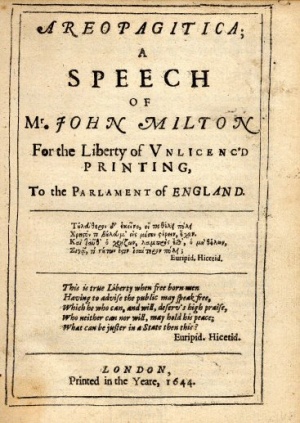

Louis-Joseph Papineau, second vice-president of the association, delivered his first great public speech since his return from exile. He took the occasion to strike the nationalist cord by making a review of the principal facts which marked the history of New France.

Yes, Messrs of the Institut canadien and Messrs of the Association canadienne des townships, I applauded wholeheartedly at your proposal, at the enlightened patriotism which inspired it to you, at the skilful organization which you will propose us to adopt; to the persevering and generous efforts by which you will achieve your holy mission. As the words God and charity contain the most concise symbol of our religious duties, in the same way the words honour, fatherland and nationality contain the principle of the highest civil virtues, the most concise symbol of our first duties as citizens. I wish, with all the ardour of the most impassioned wishes of my soul, the perpetuity of this invaluable nationality.

Our patriotic clergy, whose first dignitaries I see present here, unanimously give you its influence and its support, it is an infallible pledge of success. I see its leader, our worthy bishop1, so justly loved and venerated by all his people and all the virtuous pastors, who following his example and under his direction, educate and edify the people. I see the superior2 of the Saint-Sulpice house, under whose auspices this city was founded, this island cleared, at the price of the blood of its priests, spilled and mingled with that of the first colonists, our worthy ancestors.

Our fathers were the voluntary martyrs of their piety and their patriotism. Of their piety, founding here a regenerated society which, during a long succession of years, presented a spectacle of innocence, virtue, fraternity, perilous and untiring industry, such as the ecclesiastical annals cannot offer anything more edifying; such as the civil and military annals cannot offer anything more chivalrous in the war, nothing more daring and enterprising in the voyages of discoveries, nothing more persevering in works of colonization. They were the voluntary martyrs of their patriotism, those who, wanting that in the future the beautiful name of the Franks or Free men, the French, become grand and imperishable in the New World, as it was it in the old one, brought it in New France, knowing well that for many among them, it was to come and fall under the tomahawk, or to be burned alive on the fatal post of the Iroquois.

I see a meeting here more numerous than any other in Canada before this day. This uncommon presence of the leaders of our clergy, in a meeting dealing with temporal interests, reveals what will be the zeal and the unanimous and powerful contest of all its members; this demonstrates that they see this work as a holy work, vital and essential to the conservation of the people that it cherishes. Eh well then, these advisable ecclesiastics; you, this popular torrent who ran to this meeting and guarantees to us that the feeling which calls you here animates the universality of our compatriots; you, generous Irish missionary, who love your adoptive brothers as your national brothers, as in general they mutually like each other, and who the first called to the attention of the country the vital object interesting us all, the coming settlement of the townships, to raise to the dignity of independent farmers a crowd of those who would otherwise expatriate to become servants abroad; you, strong youth, the hope and the honour of the fatherland, who, with the voice of the devoted, the eloquent Mr. O'Reilly, began the organization of our association, you all, and me with you all, have the sharpest faith, have the most intimate convictions that this Franco-Canadian nationality is the first of our rights as men and as citizens, the most imprescriptible of our natural rights. The first cause of the nationality of each people is the mother tongue. Let each one of us ask himself how was born, how has grown the love for their nationality, they will know how was born, how strong this love is, in the hearts and the will of the 600,000 brothers of whom he is, in Lower Canada, a unit. This love is inspired to us, from of tenderest years, by the first lessons of our fathers, by the first words that we stammered: father, fatherland; by the first page on which we spelled the words God, France, Canada. It was but a feeling of the heart before we could speak. It was strengthened as our reason developed. It grew with us, everyday of our existence: during our games with the friends of our childhood; during our studies begun in the mother tongue, in our first youth, and which are continued until our extreme old age; with our first successes as young men in some career which we entered, clerical or laic; with the happy engagements of marriage; with the joys and the pains, the pleasures or the anxieties which give us in turn the arrival or the loss, the health or sickness, successes or setbacks of our children; with the great joys of the small number of days when the cause of the fatherland saw some small successes; with the tearing pains of the many more days of its so abundant hardships, of its so lugubrious mourning, which can make us say: "She lost her children, and cannot be comforted because they are no longer"3; of her so painful widowhood that, though the respect for those who suffered for it is a debt and a worship which are due to them, it is better to nourish it in our hearts and to speak of it seldom.

It grew for me, this love of the country, with all the strong emotions which I experienced. It will continue to grow with all those which I shall experience, until the supreme moment when the last pulsation of my heart will beat for the Franco-Canadian fatherland and nationality.

And my reason tells to me that my affections are well placed. All that I learned from men and books, exile and travels, by observation and reflexion, convinced me that under considerations of morality, good manners and natural talents, there was nowhere in the world a nationality better than ours. If her natural talents are not as generally cultivated as they should have been, it is the series of inscrutable decrees of the Providence which, during the long years of our minority, placed us under the supervision of a foreign power, distant, carefree, often unintelligent through its local agents, on the best means to take so that her natural talents be fruitfully cultivated; for a long time hostile to the idea that they be cultivated for good. Nevertheless they developed with a success that, in all times, allow us to advantageously sustain comparison on the pulpit, on the hustings, at the bar, and on the court bench, with what foreigners showed us to be the best.

This immense service, we owe it to our colleges, in the beautiful establishments that the kings, the Church and private individuals, in the great and old France, and the piety of our ancestors, in New France, with most far-sighted liberality, had already founded and equipped, when the colony only had ten thousand inhabitants, on sufficiently large scale, on solid enough a base for providing to all the needs for higher education, were it to have nearly two hundred thousand inhabitants; after the best directed of all our colleges, the one which was dearest to us by its importance and its glare of the services it had rendered, by the great numbers of famous Canadien whom it had educated, the College of the Jesuits, had been stolen from us. A government, bankrupt to its duties towards us, could not pay to lodge its soldiers. It found more economic to drive out the children away from the institution where, for more than one hundred years, their fathers had been trained for the practise of all virtues, and had been educated for serving the Canadien fatherland, in all fields, from the noble occupation of simple farmers to the important responsibilities of particular governors and general governors. The Longueuil, several times particular governors in Canada and general governors of Louisiana, had studied in this college. The Iberville, one of them, whose exploits are so brilliant that, if they had taken place in recent times, where the pyrrhonism of history is impossible, his feats of arms would appear impossible and fabulous, him who, in one afternoon, took three English vessels, each one of them more powerful than his in size, crew and number guns, and who boards and takes the last just in time to see his down in the sea floods, and shine forever in the glory and the records of Canada. He who carried the honor and the terror of the Canadien name in all the extent of North America, from the ices of its pole to to fires of its tropic, by fear which heroism in combat commands and by the fame which confers the genius of discoveries in the most perilous and most skilful navigations: he had studied in this college.

His brothers, the Maricourt, Châteauguay, Bienville, Sainte-Hélène, going in snow shoes from Montreal up the Ottawa river to penetrate by land after several weeks of walk, and then to make canoes to stream down to the Hudson Bay and their remove garrisons more numerous then they were, barricaded in forts furnished with guns discharged against the attackers, who had consumed what they could carry of ammunition, to obtain some needed food by hunting during such a long voyage; no longer having, to escape from death by hunger or grapeshot, but the axe to break into these forts; and capturing men and guns, by attacks so bold in apparence and successes as marvellous and strange as were those of their brother in neighbouring waters, in sight one another, in the joy of triumph and mourning of the death of Châteauguay and a great number of the heroes whom they commanded: they had studied in it.

Our families with historical names had studied there, such as Jolliet making the regular map of the St. Lawrence gulf for France, and with Marquette his tutor perhaps, going under the protection of the cross carried by the father, the peace calumet carried by the disciple, in the middle of innumerable wild tribes, in search of the father of the great waters. These first pioneers who were, not in chimerical search of the Fountain of Youth, nor in criminal extermination marches against the unhappy natives, like Ponce de Leon did, but to call these natives to the love of the Christian faith and civilizing France; bold pioneers who wanted that agriculture and the arts to one day spread out their benefits in the Mississippi valley, and who opened the road to the eight million men who, since them, walked on their path and who are indisputably, for more than the three quarters of them, the happiest portion that there is in the world of the great human family, had for one taught and the other studied in this college.

The Lotbinière, famous in the magistrature and in the arms, of which one raised these fortifications of Carillon, under which were crushed five thousand of the twelve thousand regular and militia troops, which attacked French troops and Canadian militia, hardly forming a quarter of the number of the brave men attacking them presumptuously badly directed by Abercrombie, had studied in it.

Contrecoeur, commanding at Monongahéla (the "Malengueulée" of the Canadiens), of which a handful had obtained at Fort Duquesne a greater success even, had studied in it. It is on this occasion that, for the first time, with such an amount of glare that this [George] Washington appeared, great at his beginning, when he saves the remainders of the English forces, and greater still, when later he conquers them, disperse them or makes them prisoners, a great military glory which, like that of Bayard, was always without stain, fear and reproach. The Rouville, du Saint-Ours, de Repentigny, de Beaujeu, de Boucherville, Duchesnay, de Vaudreuil, Governor General of New France, and an infinite number of other Canadiens, some famous in the Church, the army, the navy, the discoveries; the others skilful in trades and culture, in the ranks of civil life, had drawn, in this national college, the excellent education which contributed so much to the utility and the glory of the fatherland. All the comfortable families of all the parishes of the country sent their children, who, once returned within the family and the parish, repeated the learned lessons and the received examples, and formed this national character which so often tore off even to the skeptical stranger and under all other rapports, hostile, badly informed, and seeing the evil which was not, the consent that the Canadien farmers were by their manners a people of gentlemen, by their morality and their hospitality a patriarchal people.

It is this mass of much more than the nine tenth among us, who has neither reason, nor desire, nor the possibility of metamorphosing of heart nor of mouth, or of masking themselves on the outside through lieful remarks, foreign to their nationality, which saves them and which ensures their perpetuity, in a great portion of the limits of Lower Canada, that gradually they are destined to populate and settle.

The majority of the counties have no English families established within their limits. The masses have neither pressing reasons nor upcoming means of learning English. That learning English comes little by little by the ways of persuasion, is desirable; but that it be imposed by law or insult, or political inferiority, with respect to those who speak only one language, is as unjust as it is foolish. The man who speaks the two languages here is better qualified for all the duties of public life than those who speak only one: in this again the Canadiens had the advantage of the number and popularity with the masses, and there again the blind and narrow partiality of a minority government preferred discord and poverty for all the country than a just quota of power for the majority. Today it says that it wants to change its conduct; it does the opposite of what it says. It must hasten to put in agreement the practise with the sentences, so that the fatidical words "it is too late" do not become true; It must hasten, if it does not want to quickly destroy any credit in its fallacious promises.

Other countries have cities more beautiful than ours, no other has more beautiful countrysides, so judiciously distributed in long streets where houses were built close to each other. This method, better than any other, can overcome the infinite difficulties of the first clearings, road maintenance, land drying by ditches and evaporation. It keeps away the wild animals that would devour harvests. Finally, it is the very best to nourish the spirit of sociability and good vicinity. It strongly helped with the establishment of this so general practice, so useful and touching, which prevails among our farmers and established among them mutual insurance companies, without premiums, act of incorporation, lawyers nor subtle baffles, to decide when the company will repair the suffered damage. When the hurricane destroys, the fire of heaven or the negligence of men causes the burning of the house or the buildings of any one among them: of all the vicinity which is numerous, each one brings his voluntary quota of wood, hones, iron, and work so that as fast as possible his brother is restored in a house and buildings larger than those which he lost. If it happens during harvest, when his crop can be destroyed by the delay, the priest, after having given a good Sunday sermon on charity, will give a good example of charity in putting himself at the head of a large crowd to carry like the others his quota of materials or work. He will have comforted an unhappy family, built all his parishioners, but alas, also excited the anger of some foreigner, traversing his parish in a marche-donc, and writing a clever page on the horrible depravity of the Canadians, profaning the Sabbath. Finally, it makes the attendance to school, easier than it is, in the system of larger land lots, less regularly conceded and more scattered on broad surfaces.

Other countries have magistracies more skilful and more immune to appointments and political passions, than ours have been; bars, notaries, scientific and artistic bodies, superior to ours. Those were discouraged by the narrow system of a government blind and ungrateful, to which our nationality alone, which did not understand in 1775 the justice of the cause of the thirteen colonies, preserved its pied-à-terre in America. For more than 80 years, this government has plotted and entreated the ruin of a nationality which, then as in 1812, delayed the consolidation of all North America, under the glorious spangled banner.

"Sa haine se consume en efforts impuissants" 4

This nationality remained upright like a tree which, struck by lightning, lost branches which made its pride and its ornament, but which, drawing its life from the soil, reappears, after being mutilated, as vivacious and tough as it was before the passing of the storm.

These [bodies] were encouraged by national governments, which identify with all national glories, and devote the most sumptuous of their monuments by inscriptions as strongly inspiring of the highest thoughts, the most heroic devotions, of boundless love for the fatherland, above all and always, against all odds, than those, which surpass in sublimity what Sparta and Rome bequeathed us of beauty: "To all the glories of France" (Versailles) and "to great men, from the grateful fatherland" (the Pantheon), and "To those who died for freedom" (the Column of July on the place where the Bastille was).

There are elsewhere more prosperous trades, more developed industries, cultures more productive than ours; but there is nowhere a more national clergy, nor more edifying than ours, more devoted to its evangelic mission to shout: "Glory to God in highest of skies, and peace to men of goodwill on the earth, of whatever race, colour, belief they may be." This clergy is, moreover, by its legal situation, as well as by its affections and its interests, subjected to share the happy or unhappy fate of this great class of farmers, of which mainly it recruits for its ranks, with which its well-being, its existence as corporation and individual, is more closely dependent upon than in any other country. It is not here the footboard of the throne and the aristocracy; it is not reduced to, as formerly it was, in France, to replacing, in the episcopate, the purest and most majestic of men, Fénelon, by the dirtiest and most vile devil of the regency, Dubois.

It is not forced to lie, to the first of all the precepts of the Gospel, like that of England, which seizes the good of others, when it forces Catholics and dissidents to pay its teachings dearly, them who conscientiously believe that its teachings are erroneous; that they are contrary to a revelation, which they think is divine; that they are bound, if listened to, to distort their morality, and to put their eternal future in danger.

Here is the humiliating and faulty position in which, on a very high pedestals, but cemented with artifices and sophisms, the clergies are installed under the governments that want the close alliance of the State and the Church. Of the State which, inside the Church or outside of the Church, can only take good care of men's temporal interests, as soon as one is just and enlightened enough to recognize that as regards religion, each one must preserve his free will, depend upon God alone and his conscience, and not on civil law. Of the Church founded by the one who said that his kingdom was not of this world; Of the Church which can only take care of spiritual interests, of the interests for a future and happy immortality which it promises to those who are its voluntary and believing disciples. Such is the grateful mass of our farmers towards their pastors.

Thanks to God, our farmers are not grounded and grinded, as are the flocks of a State clergy. For a work of every hour of the day or night, at every moment when one comes to ask for its assistance, our clergy receives a moderate remuneration from those whom it cherishes and by whom it is cherished; whom it educated, because they like to hear it.

Our clergy is from the people, lives in it and for it; is all for it, is nothing without it. Here is an insoluble alliance. Here is the union which makes the strength; because it is free and indigenous; not founded nor of importation. Here is a pledge of indestructibility for a nationality, which is guided by the enlightened and virtuous pastors of virtuous people and trustful of them, withdrawn all and sundry from the influence of authorities, for such a long time hostile to their nationality. In 80 years, in spite of this hostility, it increased from less than 60 000 people to more than 600 000.

Now that the days of violent persecution are past and without return, it will progress faster than ever, even if the persecution was to be disguised under the baits of favour, profits and honours; because these seductions could at best work but on very few individuals in the cities. Seduction would be conscripted there. The masses, in our countrysides, will always be inaccessible to it, it cannot become contagious.

The clergy and the people in communion of doctrines, affections and interests, to which the external government is unable to participate cordially and permanently, though it can do it in troubled times, like 1774, 1790 and 1812, do not fortunately have much to ask of it. Moreover, they do not have anything to fear of its voluntary or involuntary errors, if responsible government was granted in good faith.

If it was promulgated by a far-sighted necessity, or an enlightened feeling of justice, it is the government of the majority of the people in Canada; because here there is nothing else but a people of owners, on whom this government must depend, by whom it must be directed, for whom it must act. The proletariat is so small that there would be no less cowardice than injustice not to let them enjoy the common right, and make grateful citizens out of them. It is an interior and national government; the nationality is thus saved. If it was not such in the will and calculations of those who gave it, it will become so by the fact of those who received it. The lights of the 19th century, the voice of the most powerful geniuses in Europe, of those who like the elective system, of those who hate it; those who expect much good from it, those who fear much evil from it; proclaim that there is no other possible one in America. Let us allow the penetration of the lights and the political ideas of the century in which we live; nothing could intercept them.

Let us see how much our territorial organization, regulated by the alleged oppressive government of France, is favourable to the life of peoples. We are in a fifteenth year of scarceness. Not only did it not kill a single one among us, but our farmers, constrained to order and economy, by this calamity, owe less today than they did at the beginning.

Let us see how much the territorial organization of Ireland, regulated by the government and the aristocratic Church of England, is fatal to the life of this people. Only one year of food shortage literally killed a tenth of its population, despite all the efforts and the goodwill of a State and an aristocratic Church, too overwhelmed and necessitous by their needs for luxury, which are limitless, to give effective assistance to the most pressing needs of nature which are so limited. And yet Ireland is not short of lands. A quarter of its surface is uncultivated, because it never had a national government. When it had its own Parliament, it was that of a persecuting minority, owning a third of the land, confiscated to its legitimate owners, condemning the other two thirds of the country to anarchy and sterility. Finally the humane principles of America and revolutionary France started to give birth to the love of the nationality, even inside this Parliament so faultily constituted. It spoke of pacifying and organizing; of reuniting, in the bonds of a common fraternity, the Irishmen of the two worships; those who had for centuries been exheredated from property, so precariously owned by them; those who had been placed outside the law because they were attached to the sole consolation remaining to them on Earth: their faith, without public worship, because it was proscribed. It wished that Ireland be less unhappy. This wish appeared odious to Pitt, to Castlereagh, to the Church established by the law. They entreated to the ruin of a Parliament called to the repentance of the past, to the repair of evil, the inauguration of the law and of a justice equal to all, by the pure and incorruptible voices of Curran, of Grattan and other devoted patriots. They gave to Ireland, in order to destroy this incipient spirit of nationality, a Union on the model of which ours is copied; and believed to have drowned this land of secular desolation, in its blood and its tears. Terror and embarrassment followed this great crime.

Providence, in times marked by its mercy, gave birth to the Liberator. Since Moses, no other mortal, inspired as Daniel O'Connell was, powerful in works and in words, had the consolation to lead his people, from the land of servitude, so far towards the land of peace and freedom that he promised to them; where they are about to enter, though, once again, the driver could only see it from atop the mountain, located in the wild desert, at the border of the country where oil and honey will flow; where strength and abundance will be installed, when tomorrow Ireland governs herself; to dig his people out of a state of legal inferiority, as iniquitous as that which arise from several centuries of oppression, to raise first in theory, and soon in practice, the most oppressed and humiliated of nationalities, that of Ireland, to a level of perfect equality with the one which, a few years back, was the proudest and most superb of the globe, the British nationality.

Honor to the memory of the one who gave to his nationals the teaching that they could obtain, with no other form than than that of an inflexible will, all that their interest and justice would require.

He proved, with the emancipation, that at least once he has prophetised.

Wellington said that he conceded emancipation only to fear, in order to avoid taking his sword out of its sleeve, in the midst of the horrors of civil war. This O'Connell, hitherto miraculously great with his success in favour of emancipation, was he being logical, when he retained in suspense the arms of seven million men, and said to them:

I want the repeal of the Union. I do not want to wait tomorrow, I want to have it today. I swear to you that you will have it; that you will have it in the next session, you iron-armed men, big-hearted men, men whose chests are inflated with righter angers than any of those which, in any other time, in any other place, punished the light tyrannies of the Neros of all ages; yes, light comparatively to those you supported as hereditary slaves for centuries. When you will want to blow on your enemy, to deliver yourselves of his odious presence from the whole surface of the most fertile land, the most worked by the most famished population that there is in this world. When I want it, your avenging breath on the Saxon invader, the only cause why each year you are decimated by the plague and hunger, will throw him in the sea, more easily than the hurricane drowns the wheat ball which you grow; wheat which does not save your wife or your mother, or your children, from dying of famine; but so that it provides to sumptuous superfluidities which your pitiless Masters spread out and dissipate abroad in orgies and vice. When you have the repeal, life and abundance will reappear in the green Erin, the most beautiful pearl in the seas of all creation, its most beautiful flower. But it is not yet time. Prove to Wellington that I disciplined you to be most patient men who ever suffered persecution. Prove him that my empire on you is boundless. Die, it is not time that I restore you the right to live, which you entrusted to me. I want the repeal today. The Parliament and the Duke say that they will yield it only when they are afraid of the civil war. Die, because I need to calm their worried nerves, I guaranteed them that, though they laugh at you and me, that whatever scorn which they affect for your pains and your complaints, for the laws of God and the cry of Humanity, I will chain the civil war for as long as I will live.

No, there were other rightful ways, other reasonings which would not have been as weak and contradictory as is this one. One vague, likely to throw terror in the heart, remorse in the conscience of tyrants, uncertainty in their councils, on what could suddenly burst or not burst. The other more careful, to say to those he had begun to emancipate:

Do not rise up, you will be embanked! Let us agitate, because this way we create sympathies, everywhere there are men made to the image of God, who is all kindness and justice. On the days of His pity for us, allies will come to assist us, from all points of Christendom. Then together we will say to our oppressors: "Be just or are chastised."

It is nonetheless true that the conquest of the emancipation, the triumph of O'Connell against the oppressors of his country was more unlikely, difficult and extraordinary than that of Washington on the oppressors of his own. The extent of the benefit, which was the only preliminary measure able to bring the regeneration of Ireland, has added O'Connell to the list of the most signaled benefactors of all of humanity, and the most distinguished children of his country, whose great men have been so numerous that they must be called Legion.

O' Connell promised that he would chain the civil war for as long as he would live; but he also predicted that it would be unchained after his death, if the Union was not repealed. There is no alternative. Ireland, with all Christendom for ally, wanting to have her nationality committed to the guard of her own Parliament, the choice can only be to concede the repeal or lose Ireland. Justice, justice coming too late, it is true, but justice in the end will thus be granted to this country of long-lasting pains. The Franco-Canadians will applaud to it with an inexpressible joy; then, on their turn, escaping the same sinister project of committing the guard of their own nationality to others than themselves, they will see the Irish helping them to see the triumph of the principle which they claimed for themselves. Yes, they will have the support of the Irish, who, in the elections, for a large majority have always been our friends, of these Irish who, in the press, defended the common cause of Ireland and of Canada with as much skill and patriotism as did my close friends, the Waller, the Tracey, the O'Callaghan.

The alliance between the oppressed is just and natural. The alliance between free men or men worthy to be free, from North to South, the East to the West, is just and natural. Soon the rights of peoples, in America at least, will be so easily obtained by the press, electricity, steam, the rapid exchange of the products of industry and intelligence, these new humanitarian means of progress, civilization and good government; that it is through them, more often than by the sword that declarations of the rights of man and of the citizen will be formulated; which everywhere will bare close analogies to each other, so much France and the United States acquired preponderance in deciding of the necessary recasting of almost all the European societies. The United States, by the dazzling spectacle of their prosperity, by that of the more than Roman grandeur of their near future. France, by the universality of her language, studied by all the educated classes of Europe.

Paris, with the multitude of its scientific and literary establishments, with the grandiose of its decorations, the gaiety, the knowledge, the exquisite courtesy of its salons, is the school where almost all those who, by their social position, are called upon to influence on the destiny of their respective countries, come to complete their education.

Paris, with twenty encumbered free libraries, everyday of the year, by the most enlightened men of the world, united together from all parts of both continents, with free courses, on each part of the universality of the useful and pleasant sciences, readily helping each other by the way of the election, of the instruction of foreigners, to whom France grants the greatest political and literary honours, as she does with her nationals; to the de Candolle or the Jussieu, to Blanqui, Orfila, Rossi, and Arago, Chateaubriand, Tocqueville, Lamartine, and thousand others who are all and sundry in the highest public offices, in professorships and in the Institut.

Paris, with its infinite, innumerable, contest of great men, is the powerful brain which, unceasingly and without repose, secretes, for Humanity's need, ideas of reform, progress, freedom and philanthropy. It is there that from all the parts of Europe its strongest heads and its hottest hearts run, in their desire to accomplish good for their human brothers. Disciples of the same political school, they see in same manner where to find the combination most likely to procure the greatest possible amount of good, considering the various obstacles which the current events and the various antecedents of societies oppose them. They all leave the same centre of instruction, to spread individually in their respective countries, where they bring a common pool of ideas, slightly modified by local considerations.

It is this which makes me believe that there will be the greatest analogies in the reforms requested from all parts. From all parts as well, you see the peoples for so long a time asleep awakening to their call, to the echo of their voices, which pours as much hope and consolation in the hearts of oppressed as anger and fear in the hearts of the oppressors.

Oh! for who has had happiness to live with so many great men, to obtain their regard and their confidence, the envisaged and predicted results are immense and assured. Personally, I do not doubt it, the greatest part of Europe will very fortunately be very deeply reformed.

Had not these reforms been promised in the midst of the dangers and terrors of war, by sovereigns, perjuries to the return of peace; then renouncing their engagements, in the midst of the ostentation of teir fabulous fests, with their courtiers and their courtesans? Is not the need for radical reforms obvious, by the fact that after more than thirty years of peace, of reciprocal professions between all the Christian kings, of their desire to live in peace, in holy alliance, in cordial entente, the ones with the others, they keep on foot more than three million armed men: ten times more than Augustus, Tiberius and their successors, whose paganism in the days of its more criminal excesses, commanding to an equally numerous population, and during this period of decline, without religious restrain, had to defend their empire and their tyranny. Is it not demonstrated, when, after more than thirty years of peace, all the peoples are crushed under more taxes, all governments overwhelmed by greater debts than they did when at the end of twenty-five years, of the most general war, the most fatal and most prodigious one ever to pour money like floods and blood like torrents; that the world had ever seen before these days of supreme struggle, of all the aged constitutions, united against the installation of a new social organization, the republic, without slavery, without the sensual and demoralizing worship of the last days of the Roman world?

Let us now see what our nationality was in the past, what it will be in the future.

Under the the French government, it was founded at the price of the blood of the martyrs of the faith, and the martyrs of patriotism, poured by external enemies of an atrocious ferocity; but at least peace and concord reigned internally. Once the company rule ended, the royal government, since the domination change, too often calumniated by a coarse ignorance of the facts and the remunerated spirit of adulation which replaced it, was judicious and paternal; the people, affectionate and grateful to the point of being enthusiastic, to the extent that a very great number of volunteers of more than 80 years and less than 12 years went, without being called, to the Siege of Quebec.

Under the English government, our nationality was unwanted and persecuted, from the expulsion of the Acadians to the Union of the Canadas.

Oh! the expatriation of the Acadians! It was at the same time the most cowardly political crimes in the means of its execution, and the most intrepid in its author's scorn for morals and humanity; in the carelessness of its author who attached to his name the worst infamy which ever soiled the annals of history.

One gathered the Acadians en masse, under the pretext of giving them titles to their lands, and, as soon as they had given into the trap, they were suddenly encircled by the armed forces and the subtle appearance, in the middle of the peace, on the first day of justice and joy which had been promised to them, of an immense unexpected and fleet, that would have put them down if they had tried to flee. They saw fire devouring the totality of their dwellings; admittedly the most unhappy ones there ever was on earth, in the political order; but in their social interior, the happiest ones since they were the most virtuous in the world.

These 18,000 victims of treason, and an insane fury, which depopulated its province of such a great industrial and moral population, to distribute their richest and best cultivated lands in North America to 1,800 adventurers, retired veterans, before this conflagration and this worse than vandalesque devastation, were thrown higgledy-piggledy into vessels, without attention to the unity of families, to which one said untruthfully that all would be disembarked together, and that the separated families would find themselves. They were disseminated from Massachusetts to Georgia. This Acadian nationality could not be extirpated, it strengthened ours. Its mutilated remains dragged themselves little by little into Canada, and grouped themselves around the small number of those who had taken refuge in the woods, with much more safety in the middle of the Savages and wild animals than they would have found if they had believed the proclamations and the promises of protection of a Christian and civilized government.

Together they formed, here, four of the richest, most moral, most industrious, and largest parishes of the country, L'Acadie, Saint-Jacob [of Montcalm], Nicolet and Bécancour. After 1763, France could send vessels to seek the survivors, who had remained in small number in the English colonies, and today they form in France, in the middle of very industrious populations, two communes which seldom marry in the neighbouring communes, but perpetuate as Acadians, distinguished, in the extended vicinity, by a degree of cleanliness, good culture and strong morality, which make them liked and admired.

A nationality so weak resisted the pitiless rage of such an attempt at eradication! How simple and small, those who, at this hour, plot the eradication of our own!

In Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, the same phenomenon was reproduced. Hidden in woods, saved from the extermination which the English policy had decreed, by the humanity of the Savages, a few families, after years of a common and shared life with the good Abénakis, took the risk to venture out and reappear among those they were right to call malicious, to unite hamlets which became numerous and flourished, where they restarted the primitive Acadian life, perfect model of morality, but, in the deplorable condition that their persecution made them, it is but recently that industry and good practical culture reappeared.

The dispersion of the Acadians! This political crime, the most brutal of those which occurred in the 18th century, was born in the brain and the gall of a man of a gigantic genius, as audacious in evil as in good, who gave to the history of England several of its most honourable pages, and this one, the expulsion of the Acadians, forever dishonourable to his country and his memory, the First Pitt, Lord Chatham.

The union of the Canadas, petty design without viability, morbid little runt, given birth to by what there was of political integrity, it not grand; by what there was of genius, it is not great; in the supposedly constitutional committees, in our two cities: in Mr. Ellice, assisting them with passion, to sell to people easily fooled, for the price of 150.000 louis, the lands that little a years before he was offering for less than 60,000 louis; in Lord Sydenham shareholder, or not, with the easily fooled of the salesman of Beauharnois, but in any case their accomplice, because he arrived here, decided in advances, without any comparative examination of the advantages or the disadvantages of the canal, south or north of the St. Lawrence, to throw 300,000 louis of provincial funds in Beauharnois. Doesn't the building of the road at public expense, in the north, prove that it would be more advantageous that the canal be running along side it, and that the interested parties be able to supervise simultaneously the businesses and the transports that they conduct on one or the other?

The union of the Canadas - robbery - the exact little measure of the moral and intellectual fibre of these honest people, above painted by themselves and by the acts; and of which Lord Russell made himself the subordinate, the docile instrument, leaving them the lucre of speculation and of jobbery; and taking on for him and others the shame and the responsibility of a measure which more openly invades the rights of all the colonies than would a tax on objects of general utility. He taxed them all (because what is issued against one can be against all) for the individual profit of intriguers; he taxed them in their honor, in the contempt displayed for the known feelings expressed by majorities; he taxed them all in the unconstitutional, anti-English provision establishing a civil list for five years beyond the life of the sovereign.

Union, short-lived measure, which notes or the perversity of intention of Lord Russell, or the little portée of his forecast, if he did not feel that by starting himself the plundering of Lower Canada, by giving the example, the means, the reasons and the needs to Upper Canada, to continue this plundering, he placed one of the sections with respect to the other, in the same relation where England is with respect to Ireland. If he did not see that he was giving birth to germs of hatred and discords, between populations which have the strongest reasons to help one another and and to appreciate one another, with separate legislatures; but for which there is an incompatibility of a common action with laws and interests that are as distinct as those created by antecedents, and which would become more distinct by the perpetual sacrifice of the advantages and the feelings of one of the two sections for those of the other section.

Though the foundation of Quebec City goes back to 1608, that of permanent colonization does not begin so to speak before 1634, two years after the restitution of Canada. Restitution: correct expression imposed in the terms of the treaty of Saint-Germain, by the pride of the cardinal of Richelieu to Charles Ier. In a time of peace, by fraud, Kirke his admiral, when Champlain was unaware that the war was over, had summoned him to capitulate, and the latter, yielding to famine, had gone to France carried by most of the colony.

Because it had been taken in a time of peace, it was stipulated that it was a restitution. Little time before its being surrendered to Kirke, it had been given to a trading company, which was to have the monopoly on fur trade, with the responsibility of transporting to Canada a good number of colonists. This company entered with greatest energy into the execution of this enterprise, making in two years envoys of families, mouth and war supplies, farming tools, etc, in such proportions that it had filled its engagements had taken ten years to do what it did in two years. It was during a time of war, during which Charles' unlucky star and the thoughtlessness of his favourite had pushed against the terrible cardinal of Richelieu, the true king of France, when Louis XIII but the nominal holder, subjugated by the genius of the minister. To punish the king of England, he had humiliated him first; then, later, he contributed to make him fall from the throne and to have his head cut off. He was familiar with this way of treating his enemies. He thus gave to his king a warning not to let his true feelings of hostility towards him be shown.

These first two envoys, so considerable, for the company which were taken by the English were lost for the profits of its trade and the rapid advancement of Canada. The company was so impoverished by these losses that it was not able to recover; and during nearly thirty years, it remained like its colony in a state of languor which, each year, could bring its last sigh, and ultimately its death. During this long anguish, the government of France, plunged in civil and foreign wars, forgot and neglected an establishment of so little importance. It is during this period that the Jesuits were the main boulevard, the true guardians of the colony. In their heroic abnegation and their zeal for the conversion of the Savages, and the conservation of New France, they made the greatest efforts for this mission, which was that of their predilection, because at that time, it poured more profusely than any other.the blood of its martyrs.

At the almost simultaneous arrival time of the English in Virginia, the French in Canada, of the Dutch in New Belgium, the Iroquois, the most intrepid of all the Savages in their wars, and, in their politics, the most skilful of all to nourish dissensions among their enemies, to overcome them the ones after the other, had already acquired a determinant preponderance on all the indigenous tribes, from Maine all the way to Carolina. They did not need the territory. But they were insatiable of what they called glory and triumph, which humanity would call the intoxication of ferocity, and the need of infernal and ceaseless revenge, in memory of those who who had succumbed in battle; if the calmness and dignity with which, in the defeat, they supported the infinite tortures, which they inflicted when they were winning, did not force respect for them. Their conquests only had the value of small tributes of fur skins, tobacco and wampum, signs of subjection to them; not source of profit for the winner, king of nature and men, too proud and too disinterested to depend on any person other than himself. The settlement of Europeans created needs unknown to the Savages before: that of firearms, which exalted their love of murder, that of strong drinks, which exalted it in the same way. As soon as the satisfaction of these needs was within the reach of all the indigenous nations, they poisoned, and killed one another and disappeared quickly, in spite of the human efforts of the missionaries to save those which massacred them, when the merchants killed with the eau de feu et de mort, so incorrectly named eau-de-vie, those who were enriching them.

The Iroquois were the first to get firearms, by through their traffic with Manhattan, Orange and Corlar. The most beautiful and abundant fur skins were those of the North, which was inhabited by the Hurons, the Ottawas and the Algonquins, allied to the French. The Iroquois, better armed, first made war with the tribes which had the most beautiful furs, in order to steal them to to buy more guns and brandy. The wild instinct of the Savage was over-excited as soon as he experienced the European desire to acquire.

Quebec was much more accessible to attacks by great number of wild nations than the English colonies, because the vastness of its river and tributaries made it possible to come by water, in numerous parties coming from afar, in countries covered, in all their extent, by a continuous forest, without roads nor cultivated lands and with long river navigation, large parties could not gather because of the difficulties of the walk and the impossibility to feed on the hunt. Thus located were the colonies of New England and Virginia, which quickly exterminated the Savages confined in their vicinity. Quebec, more exposed, had cultivated alliances with the most formidable tribes by their number, and the facility to come running for attacks and revenge, if they were provoked. Dominated by the Christian desire to preserve them and the care to protect them, one was long in arming them.

The Iroquois, first equipped with rifles, massacred pious missionaries and pious disarmed neophytes; and the weak French colony, isolated by these destructions and the dispersion of the remains of the allied nations, was about to undergo the same fate for a long time.

By the abundant alms collected by the Jesuits in France, they gave our fathers the bread to live and the weapons to live, by defending themselves. The missionaries joyfully parted on several occasions to meet to Iroquois, with the certainty that they would not return, that they would perish in tortures too atrocious to be described before a large public, since their reading, in the calm of the cabinet, is often filled with details too afflicting, too filled with fright and disgust for one to support. They slowed down the fury of the enemy for a few months, one or two years between the day of their arrival and the day of their death on the fatal post where they were burned. Their brothers, in Europe, solicited the kings and the powerful for help which did not come; delivered, as are too often the kings and the powerful, sometimes to their wars, sometimes to their pleasures. The French, not able to cultivate the land, where they would have been surprised and massacred, locked themselves in the forts of Québec and of Montreal, and five to six hundred people were nourished there by alms which the influence and the precaution of the Jesuits had brought from the old to the new France.

By the need of circumstances, by the eminence of the services rendered, by the unanimous assent as of these weak communities of inhabitants, the Jesuits had with the governors named by the associates: Champlain, the founder and the venerated father of the colony, noble-hearted strong-headed man, whose devotion was enthusiastic, abnegating himself, gifted of all the religious, civil and military virtues, without a stain upon his life; with Lauson and several others in Quebec City, with d'Ailleboust in Montreal, the greatest participation in the legislative and administrative direction of the colony. The little attentive historians have sometimes blamed this reunion of powers, in apparence foreign to their ministry. It was then salutary. It was necessary that all perish together, or ensure the safety of all, the safety of the nationality, by leaving the command to the most skilful, and these men were the most skilful and devoted. For a long time usefully holding power, perhaps were they slow to give it up. It seems to me that later they were sometimes wrong in their disputes, more or less sharp, with the royal governors. The fault was a little in the civil and ecclesiastical institutions, of which the attributions were then not distinct and separate enough. In Canada, in the early times, their conduct appears me to have been worthy of merit. As protectors, they were above all praise, and likewise as missionaries, being as judicious as they were zealous; as men undergoing superhuman sacrifices, exposing themselves, in the expeditions of discovery on the Mississippi, or among the Sioux, etc., with personal dangers that were nearer than those to which the Cortes and Pizarros were exposed, when walking to the destruction of the empires. They deserved unrestricted praises as a teaching body, in their beautiful college of Quebec, by the excellent studies that one made there, stronger, under certain aspects, than those which are made today. To the culture of intelligence, following the good methods they bequeathed to all our education houses, they added the theory and the practice of fine arts to those of several trades.

Later, the seminary of Quebec was its noble follower, never a jealous rival. It had the same teaching plan for the young pupils, with an almost equal success; in addition to the teaching of theology, for ecclesiastics other than the Jesuits.

It was twice burnt down; and twice the French government rebuilt it, obeying the prayers of the colonists and the governors, who saw that this house, one of the oldest and strongest support of our nationality, was being crippled with debts, that its members were missing all the necessary, were sometimes missing an abundance of food; and that to sustain a boarding school, which it nourished mainly at its own depend, giving a free instruction to procure good priests to religion and great citizens to the fatherland.

In that time of debility, shortage and fright, each year, was called into question the solution of this problem, so discouraging to our ancestors: “will we leave a posterity on this land, already soaked with the blood of such a great number of our brothers? Will we establish a Canadian nationality, or will it be exterminated next May, when the ices melt and the Iroquois arrive? ”

“If we had remained in beautiful France”, said they, “this sweet month of May would be for many among us the return of flowers, feasts, pure and fearless pleasures; instead it will perhaps be the Day of the dead and of the most throbbing tortures.” They subsided, very discouraged.

The voice of the priest calling them to the temple was shouting them: “Prepare yourselves to the passage, if God wants it, from a world of terrors, dangers, sins, and of death, to that of purity, boundless and endless love, eternal life, and eternal happiness! ”

If He lets to you live, it is for your sanctification, not that of your perdition; and you will lose your souls, if you are perjuries. You promised to God, to the Church and to France, to give them here a regenerated society and a new France. Men of little faith, do you doubt that if God wants to save you He is capable of it? If He lets us be killed, it will be only because in His kindness he will want to shorten our sufferings, and to reward us, though I fear that we did not yet deserve such an amount of happiness. You promised to found, in New France, a people more virtuous than are those of the old societies, soiled with so much dirt and crimes that your happy children will not know their names, will never know that such an amount of perversity can dishonour men who call themselves Christians.

It was by better exhortations that mine, coming from better preachers than me, to better audiences that you, that the unmarried and disarmed priest founded and preserved our nationality. Only this union of the pastors with their flocks could operate this miraculous conservation. It is no longer precarious today. It is nevertheless true that the same positive rapports between the priest and the people are still the most powerful element of its duration.

A few isolated farmers would be little wise to go and waste their time at least to listen to the infinite variety of doctrines, which contradict one another, on behalf of the hundreds itinerant preachers who besiege them.

The virtues of our clergy, the merits of a Church which, in recent times, is edifying, by virtues as sublime as those of a Fénelon, as highly placed by a genius as sublime as that of Bossuet, sustain the comparison rather well with other Churches, so that those who do not have the means of weighing and analyzing the subtleties of the thousands of those which have detached themselves from it, can live as secure, quiet and good citizens in this one in which they were born, as lived their virtuous ancestors.

May he always lend a friendly hand to all men of whatever origin, colour or doctrines, but may he not have the same obligation to open his ears and to waste his time on all subjects which do not relate to the good offices that men in society must render to each other, to soften their sorrows and their needs on the earth. May they lend a helping hand to those who could have been their personal enemies, or the enemies of their Church, or the enemies of their fatherland, if they need help: it is their duty as Christians, as they were told by their pastors. Me who speaks only as a politician and a citizen, I say that it is our duty as men, and we must practise it on any occasion, as much as it is possible for us to do. The most profound religious or political dissidences should never prevent you to do good to those who profess them.

We must blame, without reserve, the opinions that we believe bad, refute those we believe false; but that would not excuse hatred against persons. Our education and our relations have had the greatest part in the forming our opinions, we are in good faith and wish to be believed in good faith; let us make same the allouance to others. One does not seek them, when it is not pleasant to to talk only to debate and quarrel. One does not flee them when one has confidence in one's cause and in oneself.

As a politician, I repeat that the understanding and the affection between our clergy and us was and will always be one of the most powerful elements of conservation of our nationality. As it grows in merit and in services rendered, greater and more numerous, our debt of gratitude for it keeps growing. There is not, in our annals, a time when its services were more numerous than in the present one.

Our Canadian episcopate is decorated with the same talents and the same virtues as that which preceded it. Its means and its will to make do us more good have increased; and it does a lot of good by the number of its charitable and education foundations, to a extent which astonishes us.

Our worthy bishop and the seminary of Saint-Sulpice preside to the national endeavours, in which we are committed. Did they not undertake a hundred teaching and benevolence establishments which seemed above the means of the country? They succeeded in all that they undertook. Be thus assured of success. All of the clergy of the parishes will help us. It belongs to the clergy to send in the new settlements only sober, moral and hard working young people, so they proper more quickly. An old and rich parish can bare a few good-for-nothings. A new settlement could suffer from it, to that degree that clearings without progress, houses without cleanliness, cloths turned into rags would make people believe that the land is bad, and divert new colonists from settling there.

The most obvious means to safeguard our nationality, is to love it.

Unjust men, proud of their nationality, would like us to be ashamed of ours. They would scorn us with much wrong, if we were so low and vile as to believe them. To all those who would have the impudence to reproach us our nationality, let us answer that it has the most ancient, noblest and most beautiful origin that there is today in the civilized world, that of France. There are no other countries that have produced so much and such good books, nor others which can sell them at a lower price. The education which arises from this source is judged the best that there is in the world, since it is the most universally welcomed, everywhere where civilization and good taste have penetrated. France prints, for all the enlightened nations. It is from her that we receive our education, which fixes, distinguishes, illustrates our nationality.

Because she prints, as much for abroad as for home, she prints each good book in a great number of copies. A small profit on each copy compensates the author and the editor, better than in any other country. The books are sold in Paris for half that price as they are in London; with the same expenditure, we will have the means to have twice as much instruction as those of our fellow-citizens who will have taken theirs in English only. They will say that theirs is the best; we say that it is ours. It is is for foreigners to decide. Nines out of ten pronounce in favour of ours.

Since a long time the best English writers are as familiar with the French language as with their native tongue. In the latter, the English read of Hume and Gibbon but a translation, since they have written and thought their works in French5; and they are only translated with the express prayer of their insular friends, when their choice and their predilection was to write for their continental friends, as being more numerous and more suitable judges to ensure themselves a great reputation to those who would applaud their creations.

But, some will say, the English books are reprinted in the United States and are being sold there for a low price. It is true, and there are more readers among the 20 million Americans that among the 30 million English, which explains the greater pulling and the low price of America. Yes, but these books at a low price, the laws of England prevent us from receiving them. It is true that it cannot last. Free trade or smuggling will give them to us. Prohibitory laws, right next to the United States, are so irrational that they only prove the ignorance of the legislator.

Those 20 million readers will be 40 million in twenty years, then 80 million in forty years. Books will then be at a lower price in their country, than anywhere else in the world. This will ensure the prevalence of American ideas on all the others. There is not a chance in a thousand that books which will praise the benefits of the Aristocratic institution, which has become so predominant in England that it governs both the royalty and the people, will find any echo in America. Thus they will not be reprinted there. The republican prose and divine verses of Milton are of eternal duration, and an increasingly general influence.

Lord Durham notes that there are ten Canadians learning English against one English learning French, and he rejoices of this proof which he called the "anglicization" of the Canadians, what others call their "Americanization".

I am myself delighted of it, because it proves the superiority, for the needs for this country, of our educated class, over the educated class of our English compatriots in Canada, when they neglect to learn French, an additional mean to be better. I am delighted because it allows to study at the source the comparative value of the institutions which are most appropriate, some say, to the needs of an old society, with those that are appropriate for the needs of the new world. I am delighted because each year it places us in presence of talent for ambiguity and reticence; the art of speaking to not be understood, the care not to awake the idle curiosity of the people to take care of the varied interests of the fatherland and society, of the throne speeches; with the frankness, clearness, abundance of the information on the universality of the national interests, domestic or foreign, of the presidential speeches. It puts in contrast the ministerial teaching from overseas or colonial, which one cannot give a too implicit confidence to the agents of power; and the rational teaching, that one cannot supervise with too much distrust the agents of power; that there is a dangerous tendency even for the most patriotic and uninterested men; that only the precarious possession for little time, by way of election, accompanied by the greatest publicity given to all its acts and statements, which offers hardly sufficient guarantees against the abuses power.

With the most sincere attachment to our nationality, which is right, we will know, on this occasion as always, not to be unjust for our fellow-citizens of any other origin that ours, British or foreign. There is nothing exclusive in our association. When a partial policy systematically closed us access to the townships for fifty years, our compatriots must become the special object of the goodwill of a government, which can become much more quickly repairing and popular by its zeal to undo the injustices of the past, than by the title with which it will want to decorate itself. We unite for a special, but not exclusive object. Party spirit, lie spirit! It will say that our association is political, heinous toward all other nationalities, aiming to seize for our compatriots what can contribute to the happiness of a million men of other origins that ours, fellow-citizens who must be welcomed, from whater region they come from. Egoistic prejudices, now incarnated in the men of the minority who, in the past, have usurped their domination under the terms of similar prejudices.

Other associations can be formed to help with the settlement of lands by their compatriots; what is a right for us is a right for them.

The members of this association can, without objection, associate with other societies, organized like will be ours, with a similar aim, for the settlement of British or foreign nationals. We wish to cure an evil which exists against us, that to see our old settlements overloaded with population; where the land has risen to a value that is too high to be easily accessible to the poor, and even to the moderately rich. It results from this that the son of the poor is too often made a simple day labourer, or forced to expatriate himself to work for a high pay in the United States. If they were always returning, after a few years of hard work and great economy, it would by no means be an evil, it would be a great good. Plunged in a society that is more advanced, under all aspects, than is is our own, for the working classes at least, he would bring back the means to buy land and new methods, suitable to give it a greater value. It is by the comparison of the two countries and by travels, more than by any other method, that he will progress. But, for him to preserve this respect for himself, which is one of the strongest reasons to act so as to deserve the respect of others, it would be required that he offered his service only with the burning desire of leaving it as quickly as possible; to raise himself to the happy condition of a farmer intelligent, moral, comfortable, more independent, in his condition, of the influences and the requirements of others, than are the men who are placed the highest in the hierarchy of powers and dignities. For him to have the desire to become this respectable farmer, such as we know in such great numbers, in all our new parishes; men who, at the age of 17 to 18 years, without advances, took and cleared a land and, before th age of 50 years, settled on lands, each being worth several hundreds louis, five to six children; it would be needed that in the future the access to lands continue to be so easy, as it was in the past.

Such is the good that we want to provide for all men, whose special vocation is the clearing of the lands. In the circumstances of the country, yes, it is our compatriots who have the greatest need of assistance; that we direct them towards a judicious and fast colonization of the waste lands of the crown or companies; that we preferably push the colonists towards those which will be given to them at the lowest cost. No competition can thus be made to an enlightened government, that will understand that the force of the State, is the great number of citizens, rendered rich and content, by all that can retain them within the country, to attract them to settle in it, to harvest abundant crops as soon as possible, after taking possession of a land. It is is by the means leading towards this goal that it will multiply well-off consumers who will buy in greater quantity the goods of the metropolis and from foreign countries, goods that shall have the preference in the small number of industrial branches where it manufactures better and at a lower price than in England. The purchase of these taxed products will better fill the government's chest than they were when malevolence and avarice were its advisers, as they have been since the beginning of the settlement of the townships, for the common ruin of the miserly governors, judges, and advisers who, in violation of the royal instructions, which they had vowed to carry out, distributed themselves 30 and 40 thousand acres, when nobody had the right to obtain more than twelve hundred acres.

These men were there the first rebels of the country; transgressors of the laws for lucre and their own sordid profits. The iniquity lied to itself. They immensely harmed those who took and bought their lands; and have not often made the great profits which, in their ambitious dreams, were to a little later to constitute them as a territorial aristocracy, with its inalienable majorats, its substitutions and the right of primogeniture. They had understood and cared for the public good, they would have brought the lands to be granted, under the sole condition to reside on it, nearer the vicinity of the seigniories. The surplus of their population would would have penetrated the townships, without any expense or at moderate expense for the government, when there would have been a need to open very short road lines; the settlements would have expanded gradually, with all the means for happiness and success they would have procured the new colonists, located near their families which would have helped them; located close to the river on which the products of the land must be transported for their sale; where also must be made the purchase of all that is useful to the construction of public and private buildings, to the clearings, to the comfort of the families, who buy for such an expensive price the ease which they will enjoy later, by excessive work, by nature and the extent of the deprivations which accompany the painful years of the first clearing.

Instead of this judicious plan, so natural, one girdled the seigniories as if they had contained a plague-stricken population, of an innumerable nomenclature of townships, able to sustain a population of several million men, and one said, contrary to common sense, the law of nations and the Act of 1774, that the laws of the country did not apply to them and that the laws England had in toto full force and effect. This double lie had no other purpose than to intimate the Canadians that it was not desired that they should ever settle there. One demonstrated it by beginning the concessions twenty-five and thirty miles distant from their dwellings, along the American border. The low price of the lands attracted some of the inhabitants of the vicinity, who were misled by the promises of salesmen, who said to them: “We are a government skilful in speculation, and we will place all the resources of this skilful government at your disposal. Splendid roads, in prospect, and the English common law to ensure, for little work, a great ease to those who will become the free owners of two hundred acres, at the condition to be but figureheads, so that each counsellor, governor or salesman, in bulk, with brandy to the savages, becomes the fraudulent owner of thirty thousand acres, and that, from a source so pure, be soon born a hereditary titrated nobility. These sublimes designs have all fallen through. The robbers were neither enriched nor ennobled, they were only dishonoured. Their victims could not have roads because the speculators on public lands were also the speculators on the Treasury and the scrupulous supervisors of the Receiver General. It resulted from it that between the deductions this one and the wages of these other ones, there remained nothing to make the roads, nor nothing to administer the English laws. The unhappy American farmer, family father who, by the common work of ten children, had had the rare chance of creating a beautiful farm, died in despair at the prospect that perhaps it would not remain, after his death, the exclusive property of the elder, according to the admirable evangelic justice of the English law, under the protection of which he had come to seek refuge. He had seen very English judges, and made judges because they were such very passionately, ratify French abominations, ward elections done according to the forms decreed by kings of France, inventory closings, notarial acts, and thousand another useful and rational incongruities, completely foreign to English jurisprudence. If the juniors leagued with the surviving mother, not to give up the land they had cleared, which they elder was to steal from them according to the good customs of Albion, isolated model, with Upper Canada alone, of this right so full of humanity for the elders; those did not find courts of justice open to listen to them, in spite of the great itching which the judges had, who had attracted them in the trap, to say to the litigants what they had said to the purchasers. What is is a right, without the extent of the legislative, administrative and legal organizations, which give its life and effect? An abstraction. It is all which the townships ever received; and the results were that, neither the elder nor the juniors collected the heritage of their fathers; but that the alleged uncertainty of the jurisprudence and subtleties of the legal squablle devoured the heritage, and made it pass in the hands of lawyers, the sons of the judges who had made the concessions, with the prospect that they could one day return to their heirs.

There remain some difficulties of this kind for the settlement of the townships, but they will soon be overcome, if we have a government of majority and publicity.

An association like this one, which invites the population to unite in mass as a part of it, to create a considerable funds from tiny contributions from each one, can only become useful and have duration if it professes; it is not enough to say, if it proves and demonstrates that there is not the least amount of personal profit to be expected for any of its elected directors and accountants. Yes, for them will trouble and devotion be gratuitous. The utility and the lands to be taken will be for those who, with good recommendations, attesting that they love work, sobriety, and order, offer the conditions essential to be almost certain of a great success, when one begins an enterprise that is so useful to oneself and others, if it is well led as is that of clearing lands, as ruinous for oneself and those who would help the lazy and the drunkards.

Oh! the zeal with which the clergy placed itself at the head of the movement, to accredit and multiply the temperance societies, and the success which followed its creditable efforts in this measure which had become urgent, to save society from vice, depreciation, misery, domestic sorrows, frequency of crime, which intemperance all by iteself multiplies more than all the other bad passions together, is one of the recent services it rendered to our society and which, better than I would not know how to express, magnifies its titles to the recognition of the country.

The Canadian apostles of temperance knew that they were doing an incalculable good; it is to us to assist them. The association which the Canadian youth projected, and that all who have a man's heart and a Canadian heart lend the assistance of their name, of their social and political influence, their quota of contribution, as large or as sall as they want, and it will always be welcomed; of their requests towards the tepid ones and the indifferent, to win them in favour of this endeavour, not of alms, which sometimes pushes to idleness, but of judicious philanthropy and charity, which pushes to work and economy; it is the most effective means which can be employed to reap the fruits of the preaching by the Janson, Chiniquy, all those who assisted them in Canada.

Nothing more dangerous and close, to throw the youth in drunkenness and all the calamities which follow it, than the expatriation to go in service, or to go in the timber-yards. In those, exaggerated moments of work are ordered by the incontrollable brevity of a bad season lasting several weeks; one must take the wood out of the covered forests of a winter of too much of snow, in another winter, of not enough snow, during a small number of days favourable to towing. One must finish this step of the exploitation in half the time one would have given to it, in a favourable season.